Being Heedful of Process Can be as Productive as Discussion Content

Formal and informal communication between two or more of us cuts through content with barely a scratch left to the surface of whatever process we rely upon. We insatiably ravage through the ‘what’ and the ‘why’ without ever probing how the other person is coming across; their idiosyncratic manner. Yet that matters just as much—whether they articulate some point, sugarcoat it, or circle around it—because their indirect, nonverbal, and veiled communication say as much, even more sometimes, than what gets said openly.

Meetings, in general, typically lay success at the sundry feet of group dynamic, fortuitous timing, and member engagement level to somehow gel in the form of useful outputs thus received; the so-called ends. Unsure how we get to such a fortunate end, we nod our thanks to good fortune instead, just happy that we reached it. The means that got us there more often than not remains a fabled mystery.

But an unspoken question nonetheless hovers ubiquitously over our heads: how many communicative moments would have fared far better if we were more heedful of the communication process? How many brilliant insights suffered a premature death? How many bright ideas did we skip over because they seemed irrelevant to the subject at hand? Which scintillating side issues never got to plead their case because we’d neglected to return to them at an opportune time? There’s a plethora of unanswered questions like those: all of them abandoned in pursuit of some elusive lynchpin of knowledge where all eyes and ears were strictly attuned to the subject that won an audience in the form of a meeting.

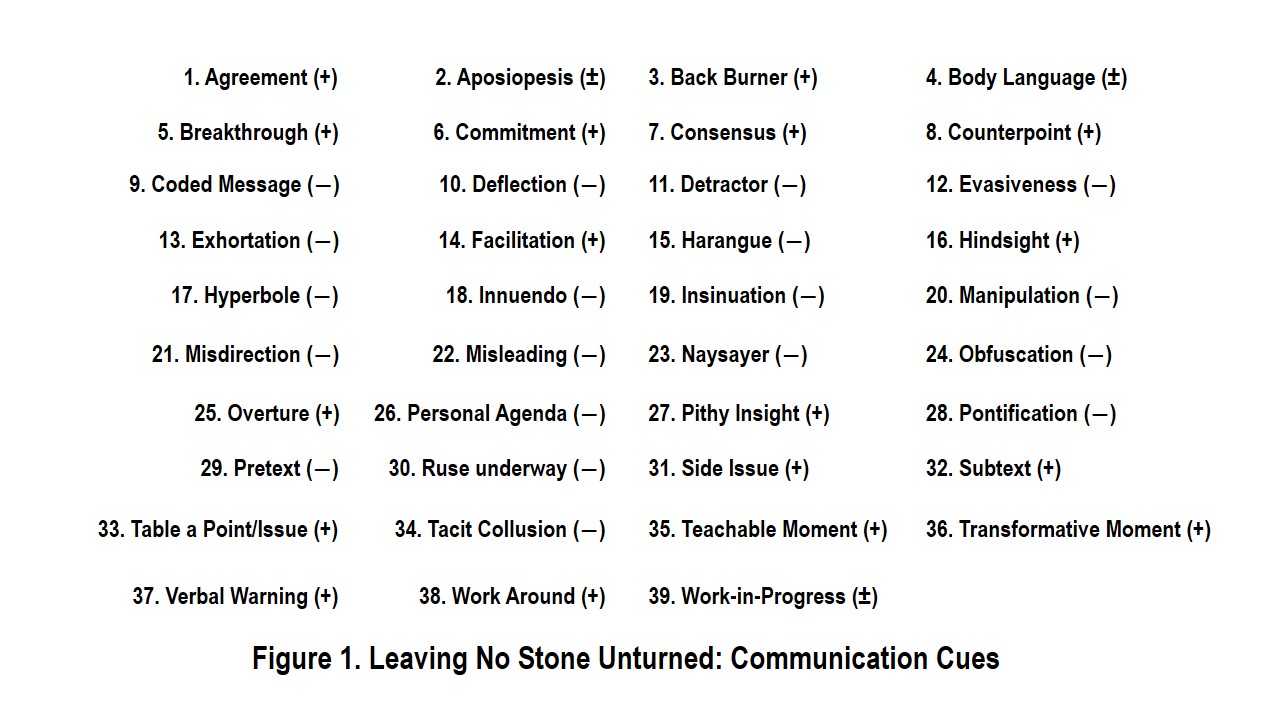

So, we unwittingly tend to ignore potentially fertile ground by not turning over the very rocks—the multifarious communication cues—that overlay it. Such cues are found to be either deleterious, inconsequential, or promising, in their usage. They’re of extreme importance, or merely good-to-know; and have incalculable, lasting value, or offer brief lifespans for actionable utility. What kinds of cues are we talking about? Below, in Figure 1, leaving no stone unturned, is a rough list that captures the gist of communication cues we either gloss over, or fail to acknowledge whatsoever, due to faintheartedness or some current subject-of-the-moment’s expediency.

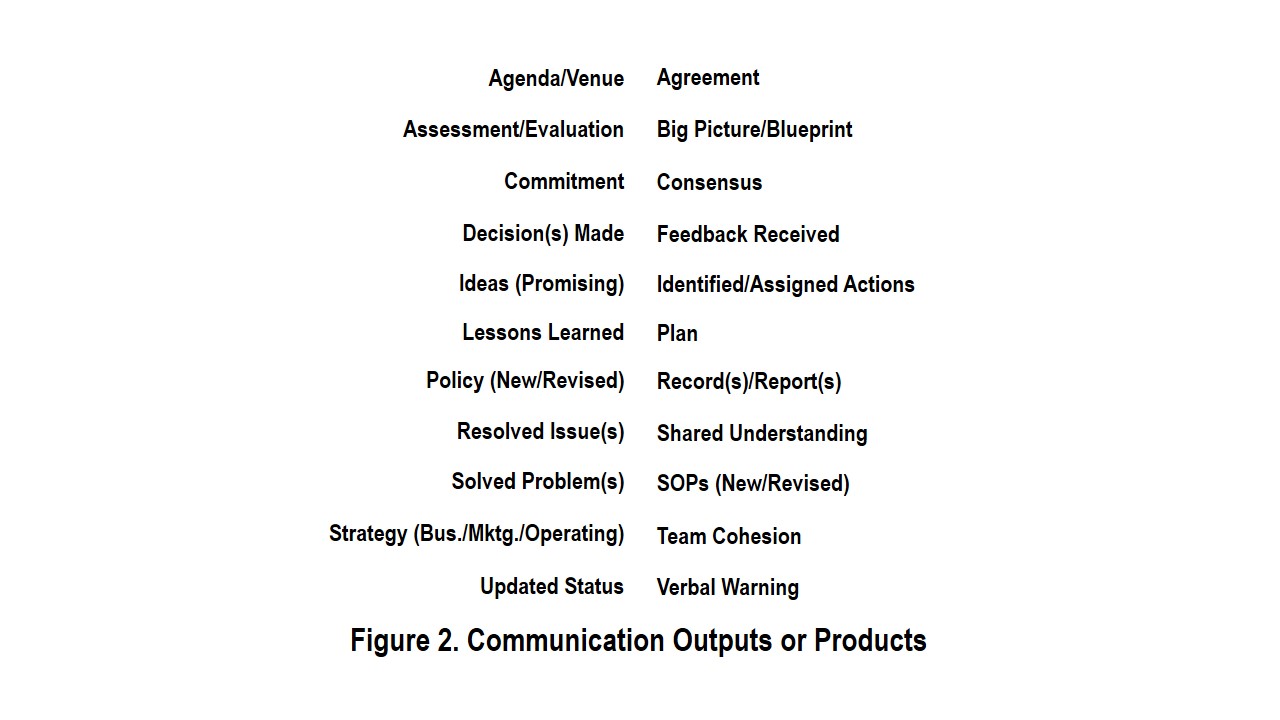

The pluses and minuses assigned to cues indicate the intention, positive or negative, in which a particular cue generally gets applied. For some, however, their usage shares similar volumes for both intentions (±). Regardless, we clearly emphasize the ends—the outputs or products hopefully achieved—over the means, the process itself. Figure 2 shows the kinds of outputs sought by dyads as well as small and large groups in all manner of communications.

Why concern over the communication process itself hasn’t seen reification before now is puzzling. Not in terms of techniques and approaches applied—which there’s clearly a burgeoning abundance of—but in terms of optimization of the process as it naturally unspools. Meaning, we need to place as much value on extrapolating, gleaning, and rescuing potential new knowledge, turning over those rocks, as we do deliberating over what’s under discussion. Thus, grooming or landscaping the process for all its worth. Why not have the best of both worlds?

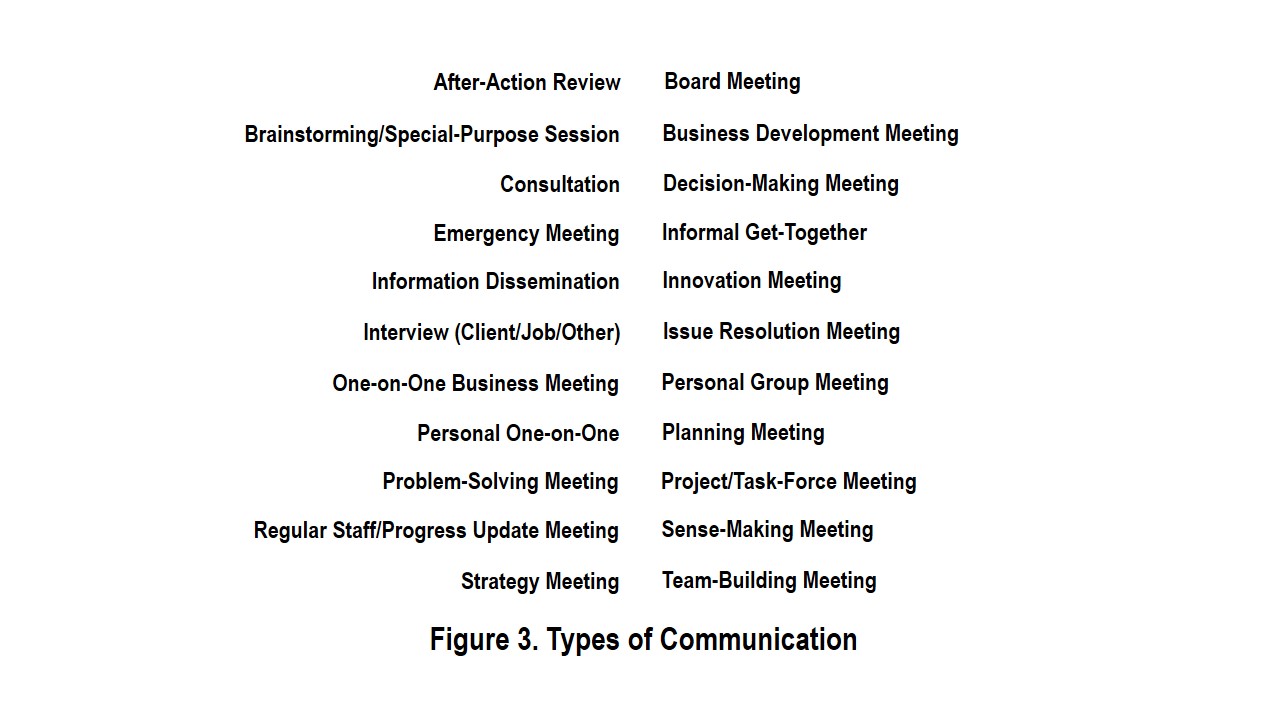

Figure 3 displays varied types of communication. Whether it’s a monologue, a dialogue, or group meeting, meaningful information gets expanded, reinterpreted, and transformed. Expressed assumptions, values, and beliefs are shared and challenged as sense-making progresses. When the process is successful, the outputs make a glad appearance. When unsuccessful, adverse outputs prove to be the fallout of missed connections between various positive and negative communication cues—those undisturbed rocks—and their unfortunate mishandlings that explicably aggregate to a bleak ending.

The downside of process grooming is that it’s attention-gorging. Staying focused on a discussion’s primary content—ever ready to contribute—demands one’s full attention without also endeavoring to apply equal vigilance for suspect-cues of potentially fateful importance. Someone has to be alert for: pruning the monotonous from the salient; occasionally blunting the negative and nonsensical remarks; fueling an epiphanic spark that’s least expected; detecting the first rumble of a sleeper idea; expanding the rarified moment of scintillating synthesis; and mindfully canceling out periodic threads of nondescript chatter: a designated rock handler capable of identifying in real-time what underlies those salient cues.

Where groups are concerned, there are four candidates for that assignment: (1) Yourself, if you’re not a major contributor to a group discussion/meeting; (2) a designated assistant with a suitable vocabulary (Figure 1) and agile mind; (3) a meeting facilitator, if their role is minimally active; and (4) another member who’s participation is relatively low, and is deemed astute and willing to act under the directed of an individual assuming control of this function: put figuratively, the architect.

The architect of the communication landscape determines actions taken, if at all, in and outside a meeting or discussion. This person will need to have the authority to act, the capacity of deciding best time to act, and possess the exceptionable fluency of how best to act. Indeed, s/he must enhance a meeting’s progress, not undermine it. From the list, below, of possible actions taken, one or more in combination will be viable, factoring in other relevant variables also in play.

| A. Ask a question | B. Call for an action/vote | C. Comment aloud |

| D. Contact after the meeting | E. Draw attention to the cue | F. Encourage more of same |

| G. Expose hidden assumption | H. Express a conclusion | I. Paraphrase/Reflect back |

| J. Put observed cue on record | K. Put a question (diversion) | L. Raise an objection |

| M. Redirect current discussion | N. Reframe as positive/real | O. Request/Suggest a break |

| P. Send e-mail/note/text | Q. Step away from meeting | R. Suggest a course of action |

15 Codified Act-Hows

Additional post-meeting actions may be needed in order to reach some final conclusion. This list covers the process-landscape architect’s immediate actions regarding how best to act. If the designated rock-handler attempted to classify each and every cue identified, the value of this exercise would fast approach diminishing returns. (1) There are three reasons for reacting to an identified cue’s presence: (i) It has obvious importance; (ii) discretion urges it be on record; and (iii) it has unforeseeable yet seemingly future implications. Which raises (2) another pertinent factor: the designated rock-handler and process architect need to be on the same wavelength, share the same sensitivities to goings-on.

For recording purposes, a record of noteworthy cued incidents might look like this:

| Cue # | (salient description)

________________________________________________ |

Act Now | Act Later | Act How |

| 6 | Avery S.: the committee hereafter assumes oversight of X | √ | J | |

| 30 | Bill T. volunteered to cover interim weekend inspection | √ | √ | J/E |

The communication cues have been codified for this reason. Likewise, so were the Act Hows, of which more than one may be rated for a single cue-instance. That way, a majority of available space is allocated to writing a memorable description of the who/what/why/when involved for every incident recorded.

In ending, it’s contended that granular parsing in real-time through discussion has more advantages than it does drawbacks. Too many valuable insights go absolutely nowhere. Have zero effect. And if things go sideways, there’s no record of how, who, and why to clarify whether the blunder was intentional, a matter of poor orchestration, or was somehow crippled by an obstruction no one can even recall at a later point. It’s equally disheartening when actionable points become pawns of pure chance. When ruses go unchallenged. Or when critical information gets sidelined, or withheld, or buried under the sediment of sustained discussion.

Communication processes are rocky landscapes whose spoken and behavioral topography require continuous cultivation, inspection, and weeding. When left unattended, the obvious result is be expected.