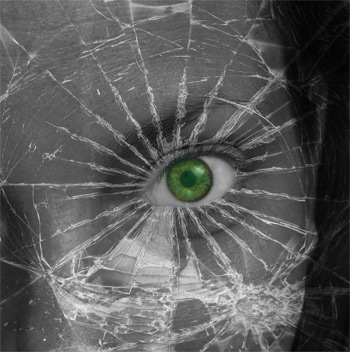

As humans we are driven to make connections, find patterns, and establish associations in places where they may not inherently exist. We are compelled to bind ourselves to the external world and have a fundamental motivation to believe that our perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors are correct. When elements of our perceived reality change or are shattered, a disconcerting sense of fundamental incongruity motivates us to reestablish a sense of normalcy, coherence, and certainty. 1 This feeling of incongruity can be deeply unsettling, for example, when men set off explosives at a marathon race or open fire in a movie theater; that is not how our world is supposed to operate. We seek to make sense of the situation and reconfirm meaning elsewhere in our lives when such tragedies occur. We need to be certain of something, anything, in moments following such heinous events.

Albeit to a lesser degree, obviously, the same phenomenon happens when we destroy an employee’s sense of certainty. For the small to mid-size business, which deals with change at disproportionately rapid rates as they grow off of a “smaller base” and come into their own, an employee’s sense of certainty is corroded at the same rate that change is mismanaged. Poorly handled change management causes employees frustration, discomfort, disengagement, and a hasty search to reconnect with other more meaningful frameworks in their lives. The fast-growing company can ill-afford the halting and even paralyzing effects of change poorly handled.

When change is happening to us, the natural instinct for us as humans is to work feverishly to reconstruct our new reality and to recover our sense of certainty about the world we are operating in. Studies show it is important for us as humans to make sense of the way things are about to be. Psychological doubt about what the change will mean leads to higher turnover and lower job satisfaction. Most importantly, organizational psychologists have discovered that if employees can’t make a link between change and their own personal goals and values (or, worse, if a direct conflict exists between them), the significance, meaning, and associated intrinsic motivation derived from work disappears. 2 Similarly, change can challenge the identities employees have built, also draining felt significance and meaning in the process. For example, plant technicians that have proudly built mastery with one machine type, for example, may find their identities as experts challenged with the influx of the next generation of machinery. Their expertise just became meaningless.

Employees simply must be able to make sense of and assign personal significance and meaning to the changes taking place, or their sense of certainty is compromised and they will resist the changes in the short term, and spiral downward in the longer term.

And the fundamental problem behind change doesn’t make things any easier. Companies are worried about sustaining the business during change, while employees are understandably worried about keeping their jobs. Interests are aligned but they aren’t mutual. This adds to the likelihood that change will be executed in a fashion that simply doesn’t work for the employee.

While much has been written on change management, what follows will focus on how to maintain a sense of certainty and how to allow employees to assign personal significance and meaning to change taking place. Being cognizant of meaning-maintenance during change is the surest way to not only bring about acceptance of the change, but to ensure the change integrates into an overall plan for sustained performance over time. In this sense, the mismanagement of change can be avoided. Here are five ways, then, to help employees assign personal significance to change and accordingly maintain meaning and motivation during the process of change management.

1) Defuse fear of the unknown – An upfront commitment to be upfront in communicating change is essential. Providing the information needed at the onset of change and even over communicating, while being honest about what isn’t known yet, what will have to be given up, and what work will be required can keep change management from negatively changing the meaning derived at work. Our minds fill in the blanks when information is lacking; new realities that employees begin to construct might be built on the wrong foundation. In the absence of proper information and context, as employees try to make sense of the change, emotional and rational reactions can swing wildly out of control. Frequent updates throughout the process of change, even when everything isn’t known, can go a long way to defusing fear. You shouldn’t underestimate the maturity of employees to be able to handle work in progress communications; nor should you underestimate the immaturity that can take hold in the face of radio silence. All in all, committing to a disciplined communication plan behind change can eliminate fear of the unknown, fear of hidden agendas, and even fear of failure.

2) Make a clear case for change – Without such a case, it will look like what change management expert Jim Clemmer calls “management by whim.” 3 An abundance of clear, sound logic can help employees to make sense of the change. Helping them understand the risk of staying stagnant vs. changing can also help on this front. With a clear cut case for change well communicated, employees can quickly buy in and move on to reconstructing their new reality in a way that enhances the personal significance they assign to the change and preserves the meaning they derive from work.

3) Frame the change – Helping employees to see how change links to their personal goals and values and how it can strengthen the identities they are building is one of the most powerful ways to maintain meaning during the change management process. Employees need to understand not only how change affects them, but how change can affect an even better version of them. Clearly linking the change to learning and growth opportunities can magnify meaning during the process. This is also true of helping employees understand how the rewards will match or exceed the efforts that will be required as a result of the change. Employees obviously play a big part as well in maintaining or bolstering meaning during the implementation of change. They may need to get out of their comfort zone, adapt their identity a bit, or adjust their goals a little.

4) Involve them in the construction of change – I’ve heard it said and found it true that a change imposed is a change opposed. Change that happens to people, rather than change they are a part of, is perceived as a loss of control. Making an effort to involve those affected by change early and often (as much and as widely as is practical) maintains the deep seated need for a sense of control. It also provides more time for those to be affected by the change to process what it will mean and how they might forge positive links to their personal goals, values, and identities. Those involved in the construction of change can also help create effective mechanisms to carry out the change in an acceptable, non-chaotic fashion.

5) Equip them for change – When people don’t feel they are ready for change, it can challenge their felt competency, which in turns effects self-confidence and strips the intrinsic motivation of work. Feeling ill-equipped for change is inconsistent with the meaning-making goals and values of learning and growing. Resources and training required should carefully be mapped out before change is even announced. And change agents can be recruited to help role model the new skills and behaviors required, thus providing much needed reassurance.