For the first time in a decade, the top tax rates for individuals and corporations are not equal. At the beginning of this year, the top individual tax rate returned to 39.6%, while the top corporate rate remained unchanged at 35%. To complicate matters, a new, separate, 3.8% Medicare tax on net investment income also became effective on January 1.

The difference between corporate and individual rates could get bigger. Congress has been considering tax reform for the past several years, and one area where both parties agree is lowering the corporate tax rate to fall more in line with the U.S.’s trading partners. This may cause the owners of a privately held business to re-examine their companies’ tax structure. Before considering a switch to a C corporation from a pass-through entity, like a partnership or LLC, it is important to consider the consequences.

A Little History

Partnerships, LLCs, and S corporations are called pass-through entities because the income they earn is not taxed at the entity level, but instead is “passed through” to the owners, and taxed only at individual rates. C corporations are taxed first at the entity level, and the earnings are then taxed again to shareholders when they are distributed as dividends.

Before 1982, privately held businesses were typically organized as C corporations, given the disparity between individual and corporate tax rates. In 1981, the top individual rate was 70%, compared to a 48% top corporate rate. The gulf between high individual rates and the much lower corporate rates invited complex tax planning, and even after the individual rate dropped to 50% in 1982, business owners stuck with their C corporation structures.

That all changed with the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which significantly lowered individual rates. Pass-throughs became popular around that time, given a business owner’s ability to limit their liability through an S corporation or limited liability company, while enjoying a single level of tax at the individual level.

Some privately held C corporations resisted the conversion to pass-through status for a variety of reasons, including administrative costs and taxes levied at the conversion. But new legislation eased restrictions on ownership structures for, and of, S corporations. In 2001, Congress made the top corporate and individual rates equal, discouraging the use of complicated structures and transactions that existed when rates were different. By 2012, the closely held C corporation, but for very few circumstances, had become very uncommon.

So what about now? The top rates are again different and poised to pull away from each other. Should private business owners consider doing the once-unthinkable: converting their pass-through business to a C corporation? This article examines the issue through the major points a business’s life cycle:

- Starting your company,

- Growing your company,

- Harvesting value from your company, and

- Selling or passing your company down to the next generation.

Starting Out

There are three fundamental tax issues privately owned pass-through businesses should consider in the face of potential lower rates for C corporations:

- Avoiding double taxation,

- The power of selling assets out of a pass-through,

- More tax-efficient gifting and other estate planning techniques available to pass-throughs.

A business owner should consider these issues in the context of cash flow needs, the ability to satisfy debt covenants, business growth plans, succession planning, and other goals a company may have.

Currently, the top corporate rate is 35%, but income under approximately $15 million is generally subject to tax at 34%. The top individual rate is 39.6%. Nonetheless, for both pass-through entities and C corporations, a business owner should consider whether the extra 3.8% Medicare tax on net investment income applies to them.

That 3.8% tax is effective for higherincome earners ($200,000 for single filers and $250,000 for joint), and applies on income that is passively earned, like interest, dividends, rents, royalties, annuities, and capital gains, unless the it is derived in the ordinary course of a trade or business that does not involve a passive investment or the trading of financial instruments or commodities. The tax, which pushes ordinary income tax rates up to 43.4% and capital gain and dividend rates to 23.8%, also applies to the pass-through income of owners who are not actively participating in the business.

Yet, even if corporate rates do not drop any further, they are still 4-5% lower on operating income, and another 3.8% lower for a business owner who receives passive income thanks to the new Medicare tax. Sure, if a business owner never intended to pay distribute earnings, sell the business, or worry about estate planning, reverting to a C corporation would be the logical thing to do.

Distributing Earnings

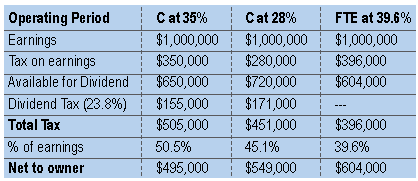

But what about real business owners who do want to harvest earnings or sell the business eventually? A pass-through entity is likely the better choice, considering the single layer of tax, even if the top corporate rate drops to 28%. Consider the following chart of a business owner, actively involved in his company, who distributes all of the earnings:

There is a clear advantage for business owners in that type of scenario to structure their business as a pass-through. In fact, even if the business owner was passively involved in the business, and thus subject to a 43.4% individual rate, he would still be in a better position than if he owned the company as a C corporation, with a 28% tax rate.

Cashing Out

The tax and economic benefits to owners selling pass-throughs are significant, notwithstanding a potentially lower corporate tax rate, and it is generally recommended that privately held businesses organize as pass-through entities for that reason.

Most buyers prefer to acquire the assets of a company, as opposed to its ownership interests, like stock or partnership shares. Acquiring assets allows the buyer to take a fair market value basis in the assets, which in turn allows for larger, future tax deductions for those assets. And if properly structured, the seller of a passthrough business can enjoy capital gains treatment on the sale of the business assets, just as if the seller had sold stock. Finally, liquidation of a pass-through is usually a tax-free event.

In contrast, the sale of assets by a C corporation will trigger tax at the corporate level, followed by a second tax when the proceeds are distributed to shareholders. That additional tax burden to the seller will typically exceed the after-tax benefit to the buyer, meaning most sales of C corporations will be sales of stock. The seller will then likely receive less for the business, because the buyer will not receive a basis step-up in the assets.

Business Succession For a family-owned business, estate planning considerations are frequently just as important, if not more important, than the income tax considerations of organizing as either a pass-through or C corporation. Whether the business itself is passed on to the next generation or sold, with the proceeds passing on, estate planning efficiency of pass-throughs, especially for businesses with strong cash flow, can be very powerful.

Most privately held pass-through businesses’ wealth transfer planning involves using both tax distributions and further distributions in excess of tax distributions to fund the payments required for the older generation owner, who is usually conveying the business through a trust, to the next generation.

Using a pass-through allows these distributions to be free of the second level of “dividend” tax, as discussed previously. That, in turn, allows freer cash flow to accomplish the planning goal, without any additional federal tax payments. Of course, proper planning depends upon the needs of the business owner: How much money will the owner need over the course of his or her life? How much control do they want over the business, as they are handing it over to the next generation?

Conclusion

The last several years have brought uncertainty and dramatic changes in estate and income tax rules, especially for business owners. It’s possible that more changes may be on the horizon, as Congress contemplates fundamental tax reform that could lead to further distortion in the top corporate and individual rates.

The decision of whether to convert from a pass-through to a C corporation is an important one that should be carefully considered, albeit is a decision that can be easily put into motion. Reverting however, from a C corporation to a pass-through is more complicated. Owners converting from a C corporation to an S corporation have to wait five years. Converting to a partnership will also usually result in enough tax liability to make the conversion moot.

But we have lived through eras of wide disparity in the tax rates on C corporations versus pass-throughs. We encourage business owners to start or reinvigorate the process of long-term tax planning, taking into account growth strategies, financing strategies, and multistate and multinational considerations, while paying close attention to business succession, whether through inheritance, gift, sale, or merger.